“Even a hunter does not shoot a bird that flies to him for refuge.”

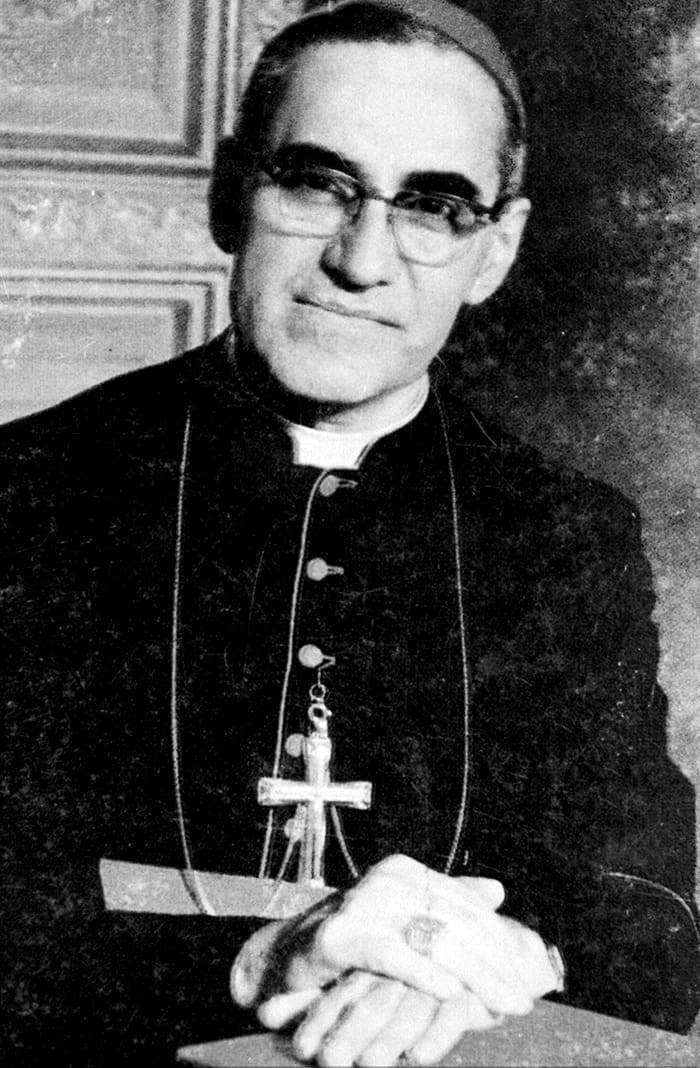

These words, attributed to a Japanese samurai proverb, perfectly capture the spirit of Chiune Sugihara—a man who, in humanity’s darkest hour, chose conscience over orders. In a world engulfed by war, where bureaucracy often served as a tool of crime, this Japanese diplomat became a quiet hero, an oasis of hope for thousands of refugees.

In July 1940, while working at the consulate in Kaunas, Lithuania, Sugihara faced an impossible choice. On one hand, he had clear orders from Tokyo forbidding him from issuing visas to people without proper destination documents. On the other, he saw a crowd of terrified people outside his window—Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi terror, for whom his signature was the only chance of survival. He chose what his heart dictated, not diplomatic protocol. For 29 days and nights, he wrote transit visas—”visas for life”—until the moment a train was taking him out of the city, and he was still signing papers and throwing them out the window of the moving car.

This story isn’t just about the number of lives saved, though it is impressive. It’s about the moment a regular person becomes an “Inspiring Soul.” Sugihara shows us that true courage doesn’t always roar; sometimes it manifests in the quiet, rhythmic sound of a pen hitting paper, against all odds and everyone. His story is a powerful reminder that moral integrity and compassion are supreme values, capable of transcending nationality, politics, and fear. In this article, I want to take a closer look at this extraordinary act of humanity to understand where he found the strength to say “no” to an empire and “yes” to another human being.

Historical Background: A World on Fire and a Trap in Kaunas

To fully grasp the weight of Sugihara’s decision, we have to go back to 1940—a time when the map of Europe was changing daily, and borders became lines between life and death. I picture this moment in history as a time of absolute darkness, where the traditional rules of diplomacy and humanity were suspended.

After Germany and the Soviet Union invaded Poland in September 1939, Lithuania became a temporary haven for thousands of Polish Jews. Kaunas, then the capital of Lithuania, was a city filled with fear. Refugees who had lost everything lived in limbo, hoping for a miracle. But in the summer of 1940, the noose began to tighten. The Soviet Union annexed Lithuania, and all foreign consulates were ordered to close. For Jewish refugees, this meant one thing: they were trapped. To the west, the Nazis lay in wait; to the east, the Soviet gulag. The only desperate escape route seemed to be a path through the Soviet Union to the Far East, but that required a transit visa.

This is the crucible of history where Chiune Sugihara found himself. He was not just some random clerk. As the Vice-Consul of the Empire of Japan, he represented a nation that was strengthening its ties with Nazi Germany (just a few months later, Japan would formally join the Tripartite Pact). This put him in an extremely delicate and dangerous position. Japan, though not pursuing a policy of exterminating Jews itself, was an ally of their greatest persecutor.

For me, personally, the most striking thing is the contrast between the rigid, hierarchical culture of Japanese diplomacy at the time and the chaos of human suffering that Sugihara came face-to-face with. In that system, obedience to the Emperor and the government was the highest virtue. An official acting on his own was unthinkable, and violating clear instructions from Tokyo—which had three times denied his requests for permission to issue visas—was an act that could destroy not only his career but also his family’s life.

Sugihara wasn’t acting in a vacuum. He saw the rising antisemitism and the brutality of the war. As an educated man who knew Russian and the political realities, he was perfectly aware that the “scraps of paper” he was issuing were the only shield protecting these people from certain death. His actions were, therefore, more than bureaucratic disobedience; they were an act of moral rebellion in a world that seemed to be losing its moral compass. It’s this tension—between duty to the state and duty to humanity—that makes the backdrop of this story so fascinating and terrifying at the same time.

The Heroic Act: A Race Against Time and Conscience

When I think of heroism, I often imagine spectacular deeds on the battlefield. But for Chiune Sugihara, the battlefield was a modest desk in a consulate, and his weapons were a fountain pen and a seal. What happened in Kaunas in the summer of 1940 is one of the most moving examples of quiet heroism in history.

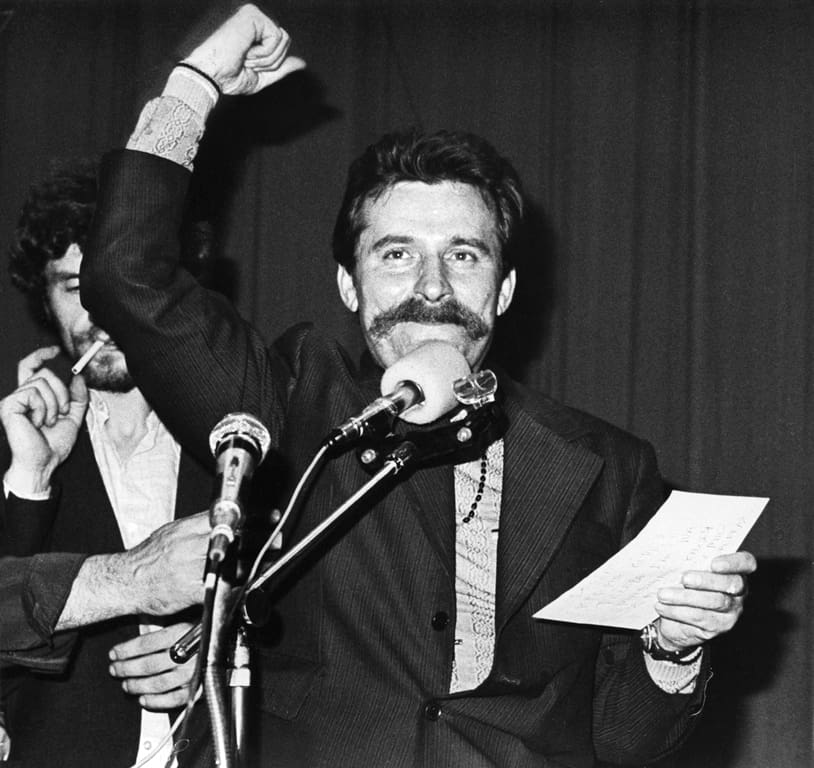

Sugihara knew exactly what he was risking. Three times he sent cables to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Tokyo, asking for permission to issue visas. Three times he was denied. The final reply was categorical: no exceptions. At that moment, standing at his office window and looking at the crowd of desperate people camped at the consulate gates—men, women, and children who, in his eyes, were not a “political problem” but human beings begging for their lives—he made a decision that changed everything.

He told his wife, Yukiko, “I have to do it. I cannot let these people die. God would not forgive me.” These words reveal the depth of his spirituality and moral compass. For Sugihara, divine law and the universal right to life stood higher than the bureaucratic directives of the empire.

When I think about this, it strikes me how easily he could have said no. He could have told himself, “My hands are tied. I have a family I’m responsible for. This isn’t my fight.” And no one would have noticed. His superiors in Tokyo weren’t expecting heroism from him, and the world was too busy with its own chaos to notice a few missing signatures. Yet, he chose otherwise. He chose to act, even though he knew he was risking everything—his career, his family’s safety, maybe even his life. It is this choice, made in the silence of his office, that makes him a true hero.

A race against time began. For the next 29 days, from morning until late at night, Sugihara wrote visas. This wasn’t just mechanical work; it was a physical and emotional marathon. Witnesses recall that by the end of the day, his hand was so swollen and stiff that his wife had to massage it so he could keep writing. Each visa was a complicated document, requiring data to be handwritten in Japanese. Still, he didn’t even stop for meals. When he ran out of official forms, he started writing visas on plain pieces of paper, hoping the border guards would accept them.

One of the survivors, Moshe Zupnik, later recalled, “We saw a man who was not only giving us documents but giving us his heart. He looked at us with a compassion we had never seen before in an official.”

Even when the consulate was officially closed and Sugihara had to move to a hotel, he continued to see refugees. The drama of the situation peaked at the train station, just before his departure from Kaunas. Standing on the platform, and then leaning out of the window of the moving train, he kept signing visas and throwing them into the crowd. In the final moments, as the train picked up speed, he handed his official seal to one of the refugees so they could forge documents and save more people.

It is estimated that thanks to his determination, about 2,139 transit visas were issued. Since one visa often covered an entire family, the number of people saved is estimated to be over 6,000. These “visas for life” allowed the refugees to cross the Soviet Union on the Trans-Siberian Railway, reach Japan, and from there, scatter across the world—to Shanghai, the US, Palestine, or South America.

Sugihara’s motivation wasn’t political or strategic. It was purely human. In a world consumed by hatred, he chose compassion. In a system that promoted blind obedience, he chose individual responsibility. His act reminds us that, in the end, we are not judged by how well we followed orders, but by how we treated another human being in need. It is this act—simple, yet monumental—that makes him a true “Inspiring Soul.”

The Aftermath: The Price of Courage and Belated Recognition

We often think that good deeds are rewarded immediately, like in fairy tales. But the life of Chiune Sugihara shows a different, more bitter truth: sometimes you have to pay a high price for moral courage, and justice can be patient but slow.

Upon returning to Japan in 1947, after spending time in a Soviet internment camp, Sugihara expected his long years of service to be appreciated. Instead, he was summoned to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and asked to resign. The official reason was staff reduction, but Sugihara and those around him knew it was punishment for the “incident” in Lithuania. For insubordination. For putting his conscience above orders.

I imagine this moment as a personal tragedy for a man who had dedicated his life to diplomatic service. Overnight, at the age of 47, he was jobless, labeled a “difficult” official, in a country devastated by war, trying to support a large family. For years, he worked odd jobs—selling light bulbs door-to-door, working as a translator, and even moving to Moscow to earn a living at a private trading company, living far from his family. He lived in obscurity for decades, unaware of the immense impact of his actions. He didn’t consider himself a hero; he simply did what he felt was right.

It wasn’t until the late 1960s that Joshua Nishri, one of the survivors who had received a visa from Sugihara as a teenager, finally found him in Japan. This meeting started an avalanche. Survivors began to share their stories, and the world slowly learned about the “Japanese Schindler.” In 1985, a year before his death, the Yad Vashem Institute in Jerusalem awarded him the title of Righteous Among the Nations. Sugihara was too ill to receive the medal in person—his wife and son accepted it on his behalf.

The comparison to Oskar Schindler is natural, though their motivations and situations were different. Schindler, a German industrialist, operated from within the system, using his influence and money. Sugihara, a Japanese diplomat, acted against the system, using only his pen and his status. Both, however, faced the same fundamental choice: to look away or to act? Both proved that one person can change the course of history for thousands of lives. Today, it is estimated that the descendants of the people saved by Sugihara number over 40,000, and perhaps even 100,000, scattered across the globe.

This legacy is a living monument to his decision. Though his own government turned its back on him and his life after the war was full of hardship, Sugihara never had any regrets. When asked years later why he did it, he answered simply, “I may have to disobey my government, but I cannot disobey God.” This story teaches us that the true value of our actions is not always measured in medals or promotions, but in the lives that continue because of them.

Lessons for Today: The Courage to Be Human

Chiune Sugihara’s story is not just a dusty chapter in a history book. When I look at the world today—full of division, humanitarian crises, and moral dilemmas—I feel his message is more relevant than ever. Sugihara holds up a mirror to us and asks an uncomfortable question: what will you do when your values conflict with comfort, career, or the expectations of others?

Modern life rarely forces us into choices as dramatic as those faced by the Japanese consul in Kaunas. No one is asking us to risk our lives to help a neighbor. And yet, the mechanisms of indifference work just the same. It’s easy to look away, to decide “it’s not our business,” that “the rules don’t allow it,” or that we are “too small” to make a difference. Sugihara teaches us that morality isn’t a matter of the size of one’s office, but the size of one’s heart.

Here are a few lessons we can draw from his example and apply in our daily lives:

1. Listen to Your Conscience, Even When It Trembles

Sugihara was not a natural-born rebel. He was a disciplined civil servant. His courage came not from a lack of fear, but from the conviction that there are laws higher than those written by men. Much like Desmond Tutu, whom I wrote about in “The Healing Power of Joy and Justice”, Sugihara understood that justice sometimes requires defiance. Tutu fought apartheid with laughter and truth; Sugihara fought Nazism with a pen and a seal. Both show that when the system fails, the burden of being a “moral compass” falls on the individual.

2. One Person Matters

We often fall into the trap of thinking, “What can I do alone?” Sugihara’s story, much like that of Viktor Frankl described in “Finding Meaning in Chaos”, proves that a single decision can have the power of a wave in the ocean. Frankl found meaning in the very heart of a concentration camp, which allowed him to survive and later heal the souls of millions of readers. Sugihara, by writing one visa, saved not just one life, but entire future generations. Every kind gesture we make, every moment we stand up for the vulnerable, has the potential to change someone’s world.

3. Compassion Over Division

Sugihara wasn’t saving Japanese people. He was saving people from a completely different culture, religion, and part of the world. In his eyes, they weren’t “others”; they were simply people in need. This universal approach to humanity is reminiscent of the philosophy of Ubuntu (“I am because we are”), so dear to Desmond Tutu. In today’s world, where we so easily build walls between “us” and “them,” Sugihara’s example is a call to radical empathy.

4. Civil Courage in the Workplace

We don’t have to be diplomats during a war to show courage. Sometimes it means speaking up in a meeting when we see an injustice. Sometimes it’s refusing to participate in unethical business practices. Sometimes it’s simply reaching out to someone who is marginalized in our environment. Sugihara shows that a professional job isn’t just about following orders—it’s also a space where we realize (or betray) our humanity.

This is where the meaning of life can be found—in discovering profound purpose in seemingly ordinary actions. Sugihara, while performing a seemingly dull, bureaucratic job, saved thousands of lives. It reminds us that each of us, even in our daily duties, has the chance to do good. It can be as simple as solving a customer’s problem with care and attention, or listening to someone who needs support. Sometimes the smallest gestures have the biggest impact—because we never know how much they can affect someone’s life.

Sugihara’s lesson is clear: don’t wait for permission to do good. Don’t worry about whether others are clapping. Do what is right, even if your hand is trembling and the world says “no.” Because in the end, as this humble Japanese diplomat showed, it’s these quiet acts of courage that save the world.

Conclusion: The Legacy of a Single Pen

To me, Chiune Sugihara’s story is more than just a tale of a diplomat who broke the rules. It’s a powerful lesson about the strength of human conscience in a world that often tries to silence it. His life proves that true courage isn’t about the absence of fear, but about acting in spite of it. Sugihara was not a superman—he was a civil servant, a husband, and a father who, at a crucial moment, decided that his humanity was more important than his career and his orders.

His legacy, preserved in thousands of saved lives and tens of thousands of descendants, is a living testament to how one person can stand against a tide of hatred. For me, he is the embodiment of an “Inspiring Soul”—someone who shows that moral integrity is not a luxury for peaceful times, but a necessity in moments of trial.

Let his story be a call to us. We don’t have to face life-and-death choices to draw from his example. Every day, we have the chance to choose compassion over indifference, righteousness over convenience, humanity over procedure. We can be like Sugihara in our office, in our community, in our family—by defending those whose voices are too quiet to be heard. We can be the ones who don’t look away.

His actions remind us that the greatest changes begin with a single, quiet act of courage.

“Do what is right, and let the consequences be what they will.”

If my writing has inspired or helped you, I would be grateful for your support.

Need support yourself? Discover how I can help you.

AI Disclosure

I see my thoughts as the essence, much like the soul, and AI helps me give them form. It supports me with research, translation, and organizing ideas, but every perspective is my own. Curious how I use AI? Read more here.